Environmental Impacts of Human Migration

How significant? (Alert: this is NOT an anti-immigrant post!)

IF YOU THINK broaching the subject of overpopulation is incendiary, try adding immigration to the broth. Doing so risks charges of extremism, racism, and xenophobia. Because there are anti-immigrant people who fit such characterization does not justify rendering the subject taboo. Besides, a fair analysis of the environmental effects of immigration could actually undermine the bigots.

It’s important to gauge the environmental impacts of all major human activities. To my disappointment, I have found little on the matter of human migration in the print media. There’s a tremendous amount on how climate change affects human migration, but almost nothing on how mass migration affects the environment.

Unfortunately, when addressing human migration, there is an overwhelming tendency to ignore its impacts on the natural environment and other life. The extensive reporting on humanitarian aspects of immigration is understandable and just. But our society’s self-defeating extreme anthropocentrism is not.

Speaking of which: much of the information presented here is from the International Organization for Migration (IOM); mainly from its recent 384-page report detailing human migration around the world. What I found disconcerting was its failure to consider how human migration impacts other-than-human life. The IOM is part of the United Nations System and stands as the leading intergovernmental organization in the field of migration. IOM is “dedicated to promoting humane and orderly migration for the benefit of all.” However, the benefit of all is restricted to a single species—us, out of some 10 million. That’s morally shortsighted at best.

❖

Population Matters

There’s little reason to continue reading for those believing that numbers don’t matter; that the quantity of humans has nothing to do with the shocking loss of wildlife and biodiversity across the globe, or with the climate crisis, pollution, etc. There are publications listed on the Population Balance website that can convince otherwise, for doubters who are openminded and willing to follow the evidence.

Simply put, the more people beyond a limited number, the stiffer the competition for basic resources and living space between humans and other life. With high numbers, humans are also more prone to overexploit wild species for food and other resources.

❖

Scope of Global Migration

Numbers and trends

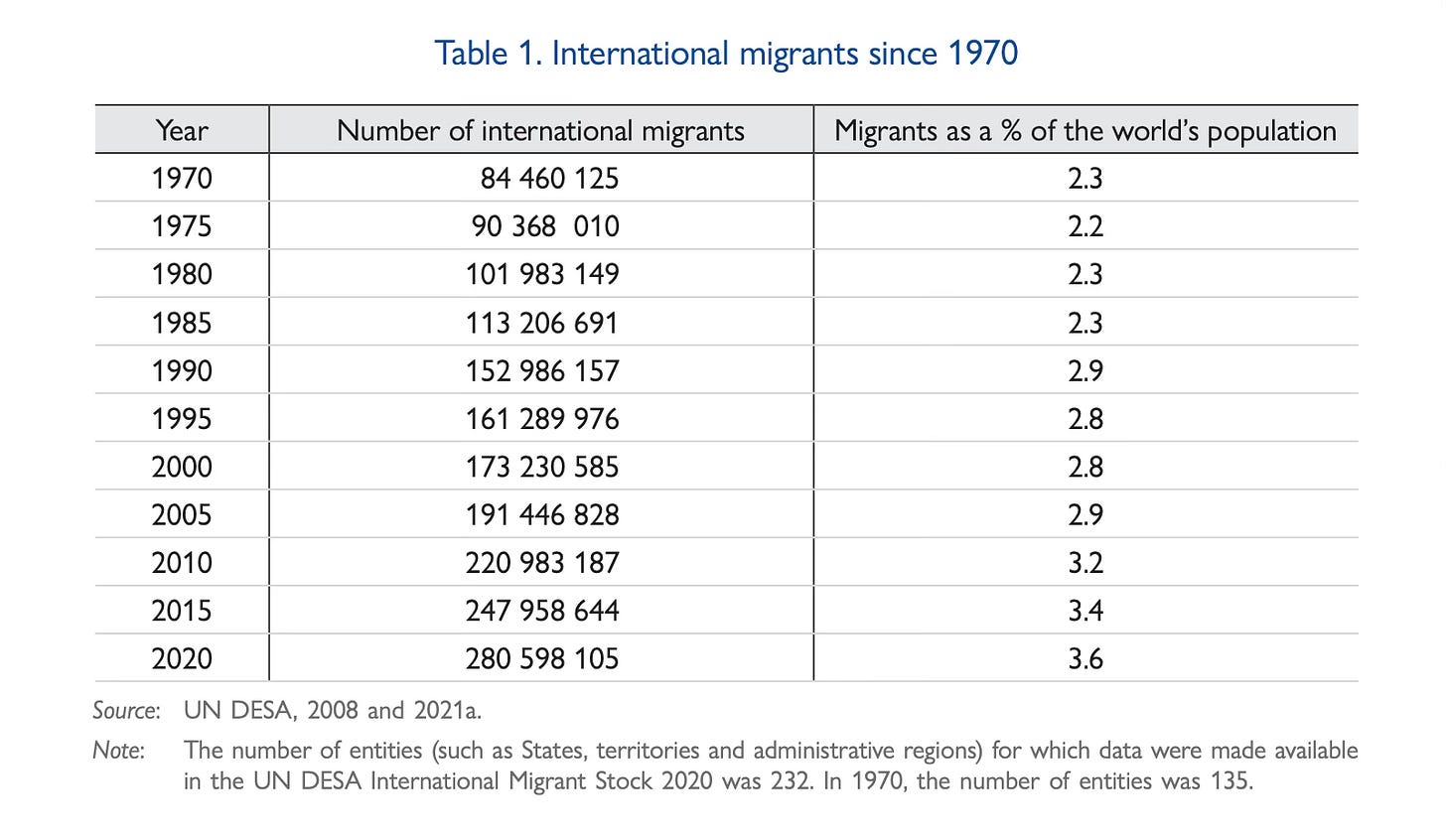

Based on IMO data, 32.6 million people migrated internationally from 2015-2020 (averaging 6.5 million per year). In 2020, approximately 281 million people were residing in countries other than those where they were born, or about 3.6% of the global population (see table). The percentage of migrants is increasing with time.

The number of settled migrants would now be approximately 312 million people (assuming 3.8% of total; slightly higher than in 2020). For perspective, this exceeds the combined populations of today’s Russia, Germany, United Kingdom, and Belgium.

Climate change is expected to accelerate migration. Within 50 years, 1-3 billion people could find themselves under a decisively unfavorable climate.

Origins and Destinations

From 1990-2020, the number of migrants from Asia increased from about 22 to 46 million (+24m), with the vast majority residing in Europe and, to a lesser extent, North America. Migration from Latin America and the Caribbean grew from roughly 12 million to 32 million people (+20m), mostly directed to North America. That from Africa rose from about 7 million to 19 million people (+12m), with most immigrants arriving in Europe. A greater percentage of people left Africa (0.9% of 1.4 billion) than Asia (0.5% of 4.7 billion) and Latin America and the Caribbean (0.3% of 647 million). Africa also received the fewest incoming immigrants.

The migratory trend as of 2024 is from regions of high fertility and population (Africa 4.0, 1.5 billion); Asia 1.9, 4.8 billion; Latin America (1.8, 663 million) to regions of lower fertility and population (Europe 1.4, 745 million); North America (excluding Mexico, 1.6, 386 million.)

This demographic trend corresponds with economic migration from less affluent regions to affluent ones. Estimates of per capita gross domestic product range from under $5,000 for the vast majority of African countries, about $13,000 for Asia, $10,700 for Latin America and the Caribbean to about $44,000 for Europe (EU) and $65,000 for North America. Overall migration is clearly from lower consuming to higher consuming regions of the world.

❖

Environmental Effects

At first glance, the act of people moving from one place to another might seem environmentally neutral. To a planetary gloom and doomer, somewhat like moving chairs around on the deck of the Titanic. But let’s have a closer look.

In-transit

“In-transit effects” can be significant especially through areas where migration persists over time. The number of people that migrate each year is likely about 7 million (see above). That’s a relatively small number of people, compared to the global population of nearly 8.2 billion. However, their environmental impact is not spread evenly across the globe, but rather concentrated along certain migratory corridors (see map). For example, in 2023 an estimated half million migrants passed through the Darien Gap, a tropical forest zone separating Columbia and Panama. Primary human migration pathways like this one often coincide with areas of the world’s highest biodiversity.

While working for the National Park Service (2006-2007), I evaluated ecological impacts along human migration routes through hot desert areas along the US-Mexico border; plants were crushed, vegetation burned, soils disturbed, wild animals flushed, and belongings and trash left behind. Others have reported similar impacts.

One may wonder about greenhouse gas emissions associated with migrants and human smugglers using aircraft and vehicles to get to their destinations, and visit or return home. It may be comparatively insignificant but, from what I can tell, has not been globally assessed.

At the origin

Emigration (out-migration) may help reduce pressure on local environments, especially if a population remains numerically stable. However, regions with highest emigration trend to have growing populations (as noted above). This diminishes the “safety-valve” effect of people leaving areas of environmental stress.

Some interesting, counterintuitive data showed that global migration, in strengthening the commercial ties between countries, impacted water resources of origin countries through exportation of water-intensive products.

At the destination

Human numbers are high, just about everywhere — Frankly, it’s difficult to say if there are any countries in the world today where significant immigration would not result in additional pressure on the environment. One might expect that immigration to countries of low population density would have less environmental impact than immigration to countries of high density. However, that would be true only if their capacities to support life were roughly the same, in terms of terrain, climate, water availability, soils, and other resources. Countries with large expanses of hot and arid climate have relatively low population densities but limited capacity for increased human numbers (e.g., parts of Australia, Western Sahara, the U.S. Southwest). There are also low-density countries with large swaths of tropical forests, like Suriname, but significant immigration to them would certainly increase deforestation.

Countries that look most promising for “environmentally friendly” immigration would be less-populated countries (e.g., Greenland, Canada, Russia) with cold climates, more natural areas, and less pressure on local resources. However, in today’s economically integrated as well as increasingly populated world, overexploitation of natural resources and ecosystems nearly everywhere is a given.

Protecting nature and the environment — Most immigration is to countries with already large populations (mainly the U.S.), high population densities (e.g., Germany and the U.K), and those that have historically been less desirable because of relatively unfavorable climates (e.g., Saudi Arabia, Russia). I’ll leave it mainly to you to decide whether or not these countries can successfully protect their environments, restore wildlife, reduce greenhouse gas emissions, and conserve nature while increasing their populations.

Let me just say that to accommodate population growth in the U.S. (65% of which is attributable to immigration), more land will be needed for housing, shopping centers, commercial and public buildings, recreation, agriculture, transportation, highways, roads, and energy development. At its current growth rate, the U.S. will add a population equivalent of today's Florida in about a decade, or roughly 21 million people. Some of this growth will come at the expense of wildlife and natural areas, be they forests, wetlands, shorelines, grasslands, or deserts. Even the IOM acknowledges that “migration, especially a mass influx of migrants, can affect the environment in places of destination. In particular, unmanaged urbanization as well as camps and temporary shelters may produce strains on the environment.”

Given that the U.S. generously exploits the natural environment and consumes resources, it’s hard to imagine how, with an increasing population, it can avoid further destroying nature, much less achieve its goal of protecting at least 30 percent of U.S. lands, freshwaters, and ocean areas by 2030 (see also).

In some ways, migrants may have less environmental impact than other residents. For instance, one widely-cited study found an association between better air quality and the overall immigrant community in the U.S. The key issue, however, is whether increased human density tends to worsen air quality, which it does.

Global effects

On population size — It might appear that there’s no “global population effect” from migration since people simply move from one country to another. However, it’s not that simple.

Immigration obviously adds people to the populations of destination countries. This is offset by population reduction in origin countries, but probably not entirely. Origin countries generally have lower life expectancies than destination countries. This would suggest that immigrants to wealthy countries would live longer and, in that way, further contribute to global population size. This longevity-gap, however, may be offset somewhat by the tendency for immigrants, at least to the U.S., to be healthier and wealthier than people in origin counties.

Out-migration from poor countries may enhance population growth insofar as it reduces local density-dependent constraints on it (disease, limited health care, etc.). Nevertheless, what’s clearly evident is that thousands of people tragically die each year while migrating. Without definitive numbers, it’s not possible to say whether migration adds to, or decreases, global population.

On climate — It turns out that countries with highest immigration (U.S, Germany, Saudi Arabia, Russian Federation) also rank among the ten top countries for carbon emissions. Globally, per capita CO2 emissions are nearly three times higher in countries with net immigration than in countries with net emigration. According to the paper’s author, “the projected decadal immigration of nearly 4 million humans to Canada, and 10 million to the USA, represent significant additional [global] challenges in reducing CO2 emissions.” Migration is highest to counties having among the largest ecological footprints; thus, the number of people added to these countries will have a disproportionately greater impact on the global environment.

I hate to pick on the U.S., but I will. It’s no small matter that my country, with by far the highest immigration, has the second highest carbon footprint after China, from which, by the way, about 18% of U.S. imports originate. Previously on Substack, I described how population growth in the U.S. cuts gains made by solar energy to reduce carbon emissions.

Incidentally, for the European Union, immigration will likewise work against efforts to cut greenhouse gas emissions and preserve biodiversity, according to researchers. They concluded that “reducing immigration in order to stabilize or reduce populations thus can help EU nations create ecologically sustainable societies, while increasing immigration will tend to move them further away from this goal.” They also note that small annual differences in immigration levels can result in large differences in future population numbers.

On resource consumption — Much is said in the media about how immigration stimulates economic growth. To the extent this is true, it’s mostly an environmental negative. Many researchers do not believe that wealthy countries can sufficiently decouple economic growth from the wide range of environmental harms to nature and the environment (historically, this has clearly not been the case).

Migration to high-consuming countries has the effect of increasing global consumption of natural resources. However, newly arrived immigrants, especially the undocumented, typically have less money to spend than other residents, although their spending power is still substantial. With time, immigrants tend to adopt behaviors of other residents including their consumption habits, for example, less healthy, environmentally less favorable diets.

What may come as a surprise to many is that “lifestyle migrants” from over-consuming countries carry their habitats to less-consuming countries. One study found that they “not only consume more energy-intensive goods than native Costa Ricans, but that their presence elevates consumption among native neighbors as well. Thus, lifestyle migration may increasingly serve as a mechanism through which unsustainable consumption patterns are transferred from the Global North to the Global South.”

Finally, migration involves “brain drain,” namely the export of more educated, talented people from emigrant countries. Consumption in countries so affected may drop, along with economic development and the quality of life for many. Globally, such diminished consumption is far offset by increased consumption from immigrant-driven population growth in wealthy countries.

❖

Limiting the environmental impacts of migration

Reduce the need to migrate, and global consumption of resources — Wealthy countries should address the tremendous economic disparity between them and less-wealthy countries. The right way to do this is to improve the lives of the world’s less fortunate while emphasizing a wholesome, sufficiency way of life for all. That means wealthier people across the world will need to cut consumption (a good thing, really). The wrong way is to attempt making everyone “rich,” which further degrades Earth’s capacity to support life.

The international community should sharply curtail war and reduce civil strife. These trigger mass migrations. It should also have in place strong contingency plans for supporting desperate migrants, and facilitating their eventual return home.

All countries should work to promote local and regional self-sufficiency in food and other essentials, and avoid unsustainable foreign debt.

Address population overshoot — High-fertility countries, with ample international support and encouragement, should adopt strong programs to lower fertility, by empowering women, advancing family planning, and promoting healthier, smaller, and child-free families.

Countries with large or dense populations should adopt population drawdown policies and adjust immigration to fertility rates to achieve that. This may require reserving immigration for refugees from war and famine, while ending it for economic reasons. Unauthorized immigration should be curtailed to avoid suffering, abuse, and death to migrants, and harms to natural areas and wildlife.

Okay, that’s a lot of should! But ignoring them won’t get people to where they need to be—namely, on a planet and in places that offer a decent life for all.

A final comment: Please don’t anyone single out immigration as the cause of the global ecological crisis. The underlying causes are overconsumption by the world’s wealthier people and excessive human numbers, both of which are increasing. These drive pollution, climate change, water scarcity, overfishing, poor governance, soil degradation, spread of invasive species, and loss of natural ecosystems and wildlife. Mass human migration can aggravate many of these problems. The solution? Scale up nature and scale down just about everything else.

❖

Coda

In today’s real world, there exists a unsettling dynamic between human consumption of resources, reproduction, freedom, and the wellbeing of the environment. For many people, this is felt at the personal decision-making level as well as by society as a whole.

If we consume more, we must reproduce less; if we populate more, we must consume less; if we limit our choices, we restrict our freedom; if we ignore all, we degrade and destroy our environment.

Yet we imagine being free to move, to bear children, and consume resources as we wish, while, at the same time, preserving a wholesome biosphere. This is a fantasy.

In the real world, fulfillment as such is unattainable. We’re forced to make hard choices, increasingly difficult ones. The sheer bulk of our presence on Earth limits our freedom and impinges sharply on that of the entire living world. Let’s abide by reality, and behave accordingly.

SCALE DOWN is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, please become a free or paid subscriber. I’d very much appreciate that. Thank you!

Eric Holle response:

This topic takes intellectual courage and insight to evaluate, and you have done a great job as usual. Reduce the need to migrate!! This is the key. Intuitively, it seems that most people would prefer to remain with their families in their countries and communities of origin, rather than engage in often dangerous travel to other countries in the hopes of being able to send some cash back to support the ones left behind. Unfortunately, US policies ranging from outright war and proxy wars to economic extortion (see Confessions of an Economic Hit Man) to "free trade agreements" can make migration a life-or-death necessity. Imagine the poor corn farmers of Mexico when NAFTA and other trade policies made it a de facto requirement to quit their traditional farming methods and adopt monocropping of GMO corn. It is simply not possible for people living traditional lifestyles to compete against today's mega-corporations that have the strength of US hegemony and international "aid" agencies behind them. Thus the need to choose between living a life of greater impoverishment or a desperate and often heart-breaking need to migrate to another country. Rather than building a border wall, we just need to respect the sovereignty of foreign countries and allow people to live as they choose.

Thanks, Tony, for a well articulated essay. It's hard to feel optimistic, particularly since so many people and leaders resist listening to common sense (a true oxymoron). I hope this gets to some of those and that they listen and respond.