❖

Last November, I posted news of conservation scientists calling for reduced resource consumption and a stabilized, gradually decreasing, human population. I found that encouraging.

Since then I’ve noticed silence on the part of other scientists, including some influential conservation biologists; namely, when given a golden opportunity, the reluctance to address overgrowth as the primary driver of the global ecological crisis. Just this past week, for example, I listened, first with delight and then dismay, to interviews of biologists Jasmin Graham on National Public Radio and Joe Roman, on Nate Hagen's podcast, the Great Simplification. Don’t misunderstand the point of this commentary. These accomplished young professionals and excellent communicators have much to offer as conservation advocates, which makes this glaring omission all the more troubling.

The interviews were very informative and engaging (and, by the way, are much recommended). However, absent mention of overconsumption and overpopulation, they blew a huge opportunity to educate hundreds if not thousands of people on the core problem of humanity’s overgrowth. My question is why?

Before turning to that, here are some highlights of the interviews; there’s a lot to learn from these guys.

The Interviews

Jasmin Graham is a marine biologist specializing in smalltooth sawfish and hammerhead sharks. She’s co-founder and president of the organization Minorities in Shark Sciences and host of PBS’ Sharks Unknown with Jasmin Graham. Her new book is Sharks Don’t Sink: Adventures of a Rogue Shark Scientist.

Graham loves sharks and the sea. She tells her story of becoming a shark scientist as a person of color and one with a “really deep connection to the ocean…this is where my food and my sustenance come from.” She shares fascinating and super cool details about sharks and other sea life.

For example, “sharks have…dermal denticles. Dermal meaning skin, denticles meaning teeth, so they have tiny teeth all over their bodies, which is such a weird adaptation…it reduces drag, keeps things from growing on it, makes them really rough. So it's hard for things to grab onto them.”

Like other sharks, hammerheads have heads with “little pores called ampullae of Lorenzini, and it helps them sense electrical charges. And by having this wide head, they can spread their ampullae of Lorenzini out further and their eyes out further… they've got an extra sense that we don't have, and it's these little pores, like little holes, just like we have pores on our face, little holes, but they're filled with jelly, which conducts electricity. It's actually open into the environment. It has these canals that go all the way to their brains, where they can actually interpret this information…[the electrical fields generated by prey]…even if they can't see the animal, they can feel its heartbeat, which is wild.”

Graham explains why sharks are “really important to our ecosystem…They are keeping the populations of fish under control, keeping the ecosystem in balance. They're also removing the weak, injured, sick fish so that they are less likely to spread disease or poor genetics and things like that, to the rest of the population. And then they also control the movements of those animals, even just by existing. So if you have a group of parrotfish and they're all grazing on a reef, if there are no predators, they will just keep grazing in the same spot until they decimate it. But if you have predators, that forces them to move around, because they don't want to get eaten.”

Shifting to our sense of deep time, Graham describes how sharks have been around longer than dinosaurs and trees, and even the rings of Saturn! She expresses much concern about their vulnerability today and emphasizes the need to protect them. “We have over 70% of our shark species that are endangered. So at risk of extinction. There are some species that have lost as much as 90% of their population.”

The NPR interviewer asks about the “damage being done to all of these marine species that you know and love so well,” and notes “it's coming from this massive global demand for marine based proteins.”

[Yes! and that demand is driven by our tremendous human numbers and innate desire for tasty marine foods, I had hoped she’d say.] But Graham narrowly hones in on the method of harvesting, avoiding the matter of excessive demand: the “big ships are out here taking our fish…it's all getting taken by all these other big corporations, and so we can't feed our families and they're out here making millions of dollars, and we're just trying to eat and we're the ones suffering….there's fishing that can be done sustainably and there's fishing that's unsustainable. And so we need to cut down on the unsustainable fishing so that our sustainable fisheries can thrive, and that people can eat.”

“We're now in what a lot of scientists are calling the sixth mass extinction event, which is largely driven by people and our impacts on the planet,” warns Graham. Her audience may wonder what to do.

If only we could achieve a sustainable society by catching our own fish.

Joe Roman is a conservation biologist and founding editor of "Eat the Invaders, a website dedicated to controlling invasive species by eating them. Winner of the Rachel Carson Environment Book Award for Listed: Dispatches from America’s Endangered Species Act, Roman has written for The New York Times, Science, Slate, and other publications. Coverage of his research has appeared in the New Yorker, Washington Post, NPR, BBC, and many other outlets. His latest book is Eat, Poop, Die: How Animals Make Our World.”

Roman is fascinated with the global ecosystem and specifically how wildlife, from the tiniest creatures like midges to mid-sized animals like bats, salmon, and seabirds to elephants and huge whales, have naturally fertilized the Earth with essential-to-all-life nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorus.

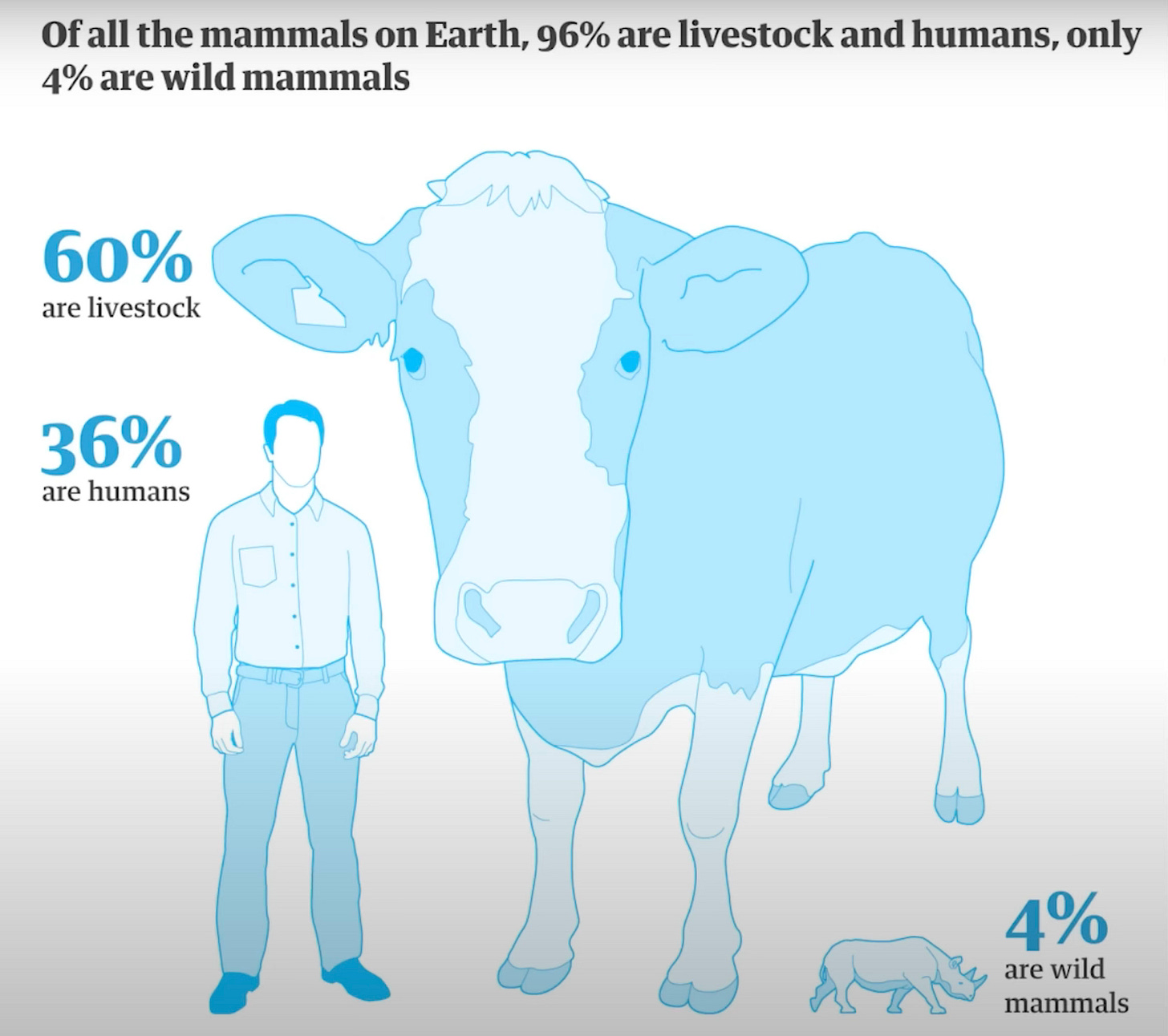

In other words, wild animals return nutrients to the land that are sent downward by rain and erosion to lakes, rivers, and ultimately the oceans. Roman and his colleague estimate that the movement of nutrients through the ecosystem has declined by an astounding 90% during the modern industrial era. He explains that, at the same time, the use of artificial fertilizers has caused many areas to suffer from nutrient overload (pollution).

If plants are the lungs of the planet, animals are the arteries, with some, like birds and whales, moving nutrients globally.

The interviewer turns to the need for a more sustainable society that has slipped beyond humanity’s reach by massive exploitation of the world’s resources. In response, Roman describes the ocean’s amazing food web that’s been compromised by humans, assuring, however, that “it doesn’t have to be that way, there are ways we can be part of the ecosystem.” He humorously suggests, for example, that human remains, instead of being buried, could be used as fertilizer. The same goes for human pee and poop.

Roman is totally into restoring ecosystem integrity to benefit people as well as other life. He views wild animals as allies, noting, as if to avoid disquieting his audience, that “they just need to be a little bit more abundant.” Despite the general downward trend in wildlife, Roman finds hope in reversing declines, citing the comeback of seals in New England and restoration of sea otters on the West Coast. The latter instance triggered return of kelp forests as the otters culled overabundant urchins that suppressed the forest. This in turn boosted fish populations and those of other animals across the food web.

The interviewer mentions the problem of plastic in the ocean and its impact on sea life. Roman says we must get a handle on this problem, and that far more financial resources and expertise are needed to address the broader crisis of marine pollution. One solution is good “story telling” about wildlife and life processes to reach the widest possible audience. His hope is that more people become directly involved with wildlife, pointing, by way of example, to those in his Vermont community who physically move salamanders and frogs across roads to save them, and build “amphibian crossings,” such as large culverts under roads.

Roman sees positive cultural trends in our society; for example, a shift in today’s young people toward thinking more about the rights of the animals themselves, apart from their benefits to society.

As for solutions, he favors on-the-ground learning and local actions to help wildlife, and at the societal level, greater focus on climate, social equity, biodiversity and other matters, but not mentioning overconsumption or overpopulation. If he had a magic wand, the one thing he would do is have us get back to zero human-caused extinction. That would seem, nevertheless, almost unimaginable without scaling down the human enterprise.

Stiff-arming the Elephant in the Room

During the interviews, why didn’t these well-spoken scientists take a moment to explain to listeners the tight connection between the tragic loss of the world’s wildlife and our overgrowth problem? How can our society fulfill their dreams of restoring life on Earth without addressing the root cause of the ecological crisis? More broadly, why is it that many nature advocates shy away from educating the public on the twin threats of overconsumption (by the affluent) and global overpopulation? Here are five likely reasons:

Hypocrisy. It’s hard to speak out against a problem that one’s part of. If we’re to address overconsumption, it’s hard to live the affluent lifestyle, or travel freely to distant professional events and vacation spots. If we have multiple children, we’ll certainly be uncomfortable about bringing up overpopulation. These are the dilemmas of many nature advocates. So, what to do? First, don’t avoid speaking out on these core issues. Second, draw down personal consumption and, if the desire for another child is paramount, adopt one. Third, and very importantly, be an honest hypocrite by admitting that one can and should do better. No one’s perfect, people get that.

Fear of sounding racist, eco-fascist, or anti-human. We can avoid this by being clear about misguided population control policies that have harmed people in the past, and by addressing overpopulation in an anti-racist context. The Center for Biological Diversity has valuable suggestions for doing so. For further guidance, Population Balance offers “an anti-oppression lens to draw connections between pronatalism, human supremacy, and ecological overshoot, and offers solutions to address their combined impacts on the planet, people, and animals.” In short, there are ways to deal with any stigma attached to promoting progressive population policies, and smartly respond to the harshest of critics. We can’t ignore or deny overpopulation because it’s challenging to speak out about this matter. As for overconsumption, it’s relatively easy to draw the connection between it and existential harms to both human and non-human life. There’s no endeavor more quintessentially pro-human than curtailing deadly overconsumption. All that being said, speaking against overgrowth — be it population or economic—could in some circles potentially risk one’s career advancement or grant opportunities. But failure to do so for this reason should be, for the genuine nature advocate, morally unbearable.

A belief that nature can be restored without scaling down humanity. Some nature advocates draw this erroneous conclusion by vastly overestimating society’s ability to compensate for the accelerating loss of wildlife and natural ecosystems. They point to instances of species recovery, and successes at abating pollution. While it’s true (fortunately!) that there are some success stories, their scope is limited. Given the immense scale of human activity, the overall downward trajectory of the natural world continues. Even if humans were to dedicate half the planet to nature, some 15-20% of species would likely disappear. This widely-discussed “Half Earth” proposal would almost certainly require shrinking the human enterprise. My sense of it is that people working for large resource agencies and conservation organizations implicitly, if not overtly, subscribe to an alluring “can do” belief for reasons of mental comfort, politics, and conformity. In other words, it behooves one in such circumstances to be unrealistically optimistic rather than realistic.

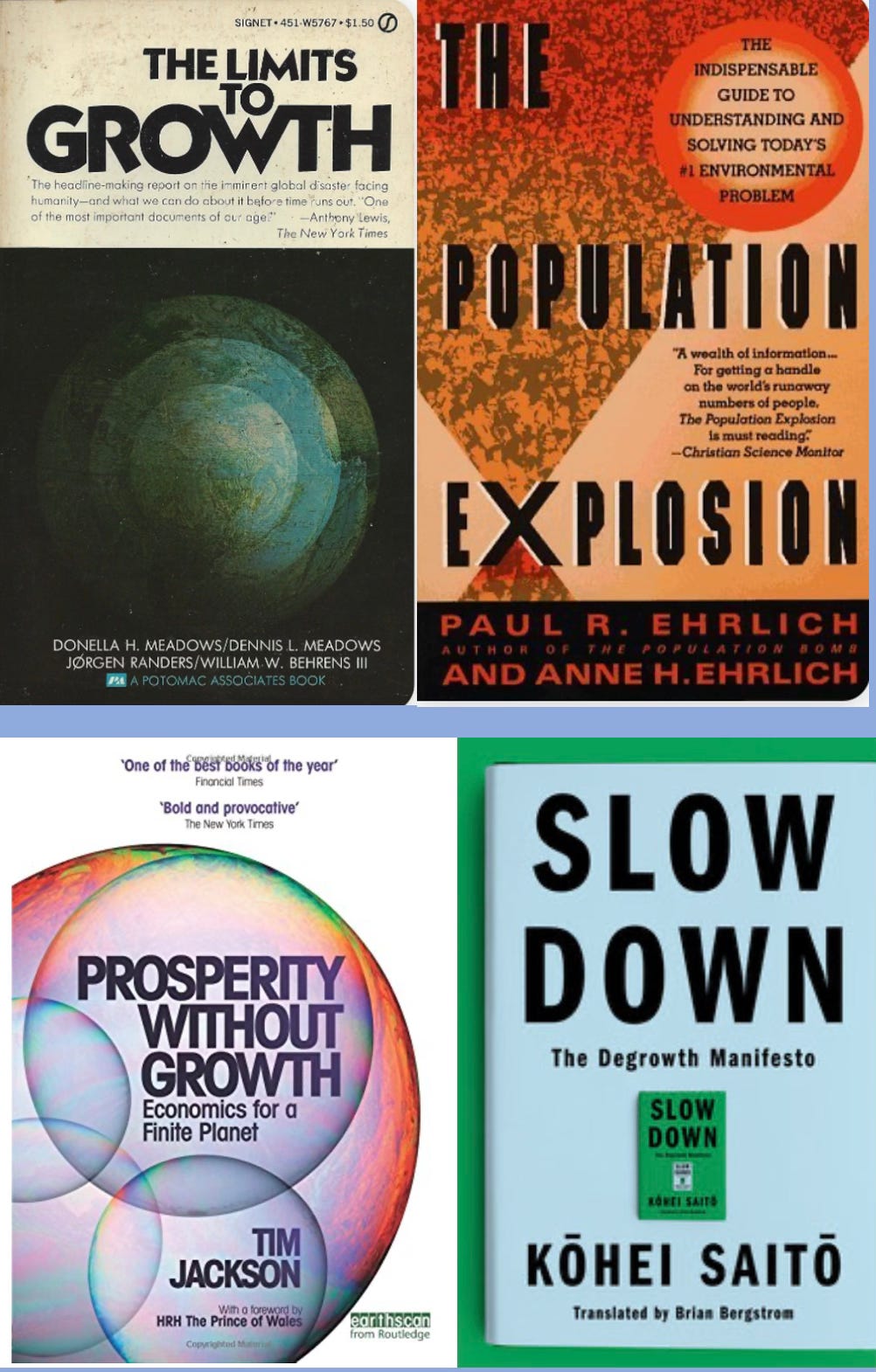

The belief that population and economic reduction is not possible. This is perhaps the most self-defeating belief for a nature advocate. To some, the only recourse is to protect whatever natural areas we can, mitigate pollution to whatever degree possible, and have faith in new conservation technologies, laws, and renewable energy rather than anguish over the elephant in the room. However, ignoring systemic competition between humans and other life for resources and living space, the toxicity of runaway capitalism, and the tendency of billions of ill-informed people to pursue wealth as a lifestyle priority over nature dooms our advocacy to ultimate failure. We can’t limit our vision to only what’s possible under the global growth paradigm and expect to restore nature. “Degrowth”and “Sufficiency” are emerging social movements that have great potential to make us winners, not losers. Conservation scientists, animal advocates, and nature lovers all need to enlist and help shape them.

A sense that challenging overgrowth is no longer fashionable. To some people, the matter may seem faded and tattered. Books like The Limits to Growth (1972) and The Population Explosion (1996) have long weathered attacks by critics yet appear, to some, out-of-date. I doubt this is a generational thing. It more likely reflects inattentiveness to solutions that are being advanced today (see below), something that could turn on a dime.

❖

Today there is growing scientific consensus that we have now vastly overstepped earth’s sustainable limits–not least as regards our climate system. Despite this, most leaders continue to seek more growth as the answer to our problems. After years of research and contemplation, in her 1992 update Beyond the Limits, Dana Meadows argued the problem is not a lack of evidence, but rather, the lack of an alternative vision. She put forward that to create a sustainable world we must replace the growth paradigm with a new vision of prosperity. — Katherine Shields, climate and systems change educator and co-founder of the Vienna Doughnut Coalition (2023)

Humans are enamored of humans. We think we are the greatest thing that ever happened to the planet. But we are actually not that, and in many ways agent Smith in the Matrix was right to call us a cancer. I don’t know why we think we’re so smart because we obviously aren’t. Smart people wouldn’t get into this incredible situation that we’re in where we’re destroying our planet. We’re certainly not beautiful. Many animals are much more gorgeous than we are. I don’t think we have anything to be particularly boastful about. Why can’t we just fit in? Why do we have to see ourselves as some kind of triumph of evolution? We need to adapt to the planet we’re on, which means we have to adapt to limited resources. Why is that so hard? Because we are inherently a flawed species. We rose to power over other homonims (Neanderthal, Denisovans, etc—about 10-15 of these) simply because of our numbers and our aggression. We have nothing to be proud of. And I’m speaking of us as a species (homo sapiens), not of particular “races” (differences derived from geographical adaptations).

Excellent commentary, Tony.