Why did the Ivory-billed Woodpecker and not the Pileated Woodpecker go extinct?

And why it's important to know.

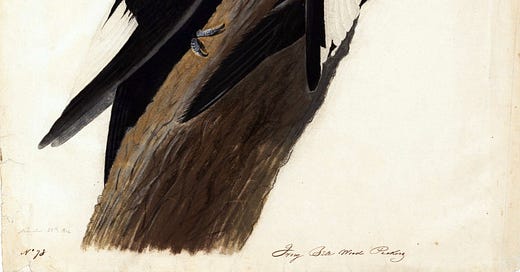

The majestic and formidable species in strength and magnitude, stands at the head of the whole class of Woodpeckers…His eye is brilliant and daring; and his whole frame so admirably adapted for his mode of life and method of procuring subsistence, as to impress on the mind of the examiner the most reverential ideas of the Creator. — Alexander Wilson, circa 1790.

HOW CAN IT BE that wildlife is disappearing when many wild animals like raccoons, white-tailed deer, crows, and even alligators seem to be thriving?

Yes, it’s shocking to read the awful news about sharp wildlife declines in the U.S and around the world. But how can most people be expected to fully grasp what’s happening when gray squirrels, mourning doves, and others still abound?

In other words, how do we make sense of the fact that some wildlife are in big trouble while others prosper? How can we help people understand which trend will prevail?

For a deep dive, let’s compare two large North American woodpeckers, both associated with old growth forests: the extinct Ivory-billed Woodpecker and the extant Pileated Woodpecker. Why is the latter still here, and the other not (or most probably not)?

Two Woodpeckers, Two Different Outcomes

Let’s begin with geography. Animals that naturally occur in small geographic areas are typically more vulnerable to extinction. However, historically the Ivory-bill Woodpecker was not particularly limited in this regard. While Ivory-bill range was much less than that of the Pileated Woodpecker, it was still extensive (see maps). Ivory-bills occurred in over a dozen states.

If geography can’t explain the Ivory-bill’s disappearance, might something have happened to forests across the southern U.S. that eliminated Ivory-bills while allowing Pileated Woodpeckers to persist?

Indeed, over a century of forest cutting dramatically changed the southern landscape. Most observers are certain that habitat loss was the chief reason why Ivory-bills disappeared. Specifically, the elimination of forests with a prevalence of large “old growth” or mature trees, with a lot of dead and dying wood. Big trees and huge snags are believed to be key features of Ivory-bill habitat. But guess what—the same holds true for the Pileated Woodpecker!

One has to dig deeper in trying to understand why, upon considerable deforestation, the Ivory-bill Woodpecker disappeared while the Pileated didn’t. Was it a matter of diet? Well, maybe.

According to the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ivory-bill Woodpeckers mostly ate large larvae of longhorn, jewel, and click beetles, and to a lesser extent those of smaller bark beetles. But here’s the catch: accounts of Ivory-bill diet were based on anecdotal observations and the examination of the stomach contents from just eight collected birds.

If indeed the Ivory-bill Woodpecker required a diet of large beetle larvae, that may have disadvantaged them. These insects likely declined in abundance when people cleared areas of dead and dying trees that were naturally created by wildfires, floods, and other disturbances.

As for the Pileated Woodpecker, its primary food is said to be carpenter ants, supplemented by other ants, beetle larvae, termites, and other insects such as flies, spruce budworms, caterpillars, cockroaches, and grasshoppers. (Both woodpeckers also reportedly consumed wild fruits and nuts.)

Yet a search on Google Scholar tells me that studies of Pileated Woodpecker diet are mostly from the western U.S. where carpenter ants abound. Suffice it to say that Pileated Woodpeckers take mostly large insects from decaying wood and aren’t too picky. But there’s no solid evidence that Ivory-bills were radically different in this regard.

Any disadvantage of a diet mostly of large beetle larvae (if, in fact, that were the case) would be heightened by Ivory-bills being bigger than Pileated Woodpeckers. Other things being equal, the larger an animal is, the larger the area it needs to find enough food and other resources, such as suitable nesting trees.

Consider this: the Ivory-bill’s overall length was about 19-20 inches. They weighed 1-1.3 lbs. By contrast, the Pileated Woodpecker is typically about 16-19 inches long and weighs about 0.6-0.8 lbs.

And so, Ivory-bills needed larger foraging areas than Pileated Woodpeckers. This made them more vulnerable to habitat shrinkage and fragmentation caused by logging and other factors. Based on size, Ivory-bills may have required a home range of up to 20 square miles per pair to find enough food. By comparison, territories for Pileated Woodpecker reportedly ranged from a mere 0.2-0.6 square miles in Missouri. (But territory size can differ from that of home range size. Surprisingly, I could find little information on home ranges for Pileated Woodpeckers in the southern U.S. In the Pacific Northwest, they vary from about 1.5 to more than 3 square miles).

The Ivory-bill’s larger size meant it also needed somewhat larger nesting cavities and perhaps bigger nesting trees (that were becoming less common). Ivory-bill nest openings were roughly 5 inches wide, compared to those of the Pileated Woodpecker which are typically under 3 1/2 inches wide.

Nonetheless, can the size difference between Ivory-bills and Pileated Woodpeckers by itself explain why one vanished and not the other? Not really. There are other large woodpeckers that, like the Ivory-bill, weigh over a pound but are not extinct. The Black Woodpecker with a broad geographic distribution across Eurasia seems to be doing okay. The Great Slaty Woodpecker in Asia, while declining and vulnerable, is still around. Granted the large Imperial Woodpecker in Mexico, like the Ivory-bill, is almost certainly extinct.

Well, where does this leave us? A smaller geographic range, a more restricted diet, and a larger body size are all factors likely to have contributed to the Ivory-bill’s greater vulnerability to extinction.

Perhaps there’s one more thing—hunting of Ivory-bill Woodpeckers by people. Ornithologist Noel Snyder argued that, in fact, “ivory-bills are not foraging specialists (they ate nuts and fruits as well as beetle larvae), they were once common rather than rare birds within their habitat, ivory-bills declined in and disappeared from many regions before virgin forests were cut, and ivory-bills were shot not simply by skin collectors but also much more extensively for food and sport.” Nonetheless, these observations don’t refute the habitat loss explanation as to why the Ivory-bill Woodpecker disappeared. For sure, hunting didn’t help and could have triggered and then accelerated the Ivory-bill’s demise.

By the way, I’d like to add that sometimes there are striking differences in how similar species behave around people. Some are much more likely to flee. This costs them in terms of health and metabolic energy that would have to be made up by eating more. Perhaps Ivory-bill Woodpeckers were more stressed out.

Why might Ivory-bills have been more fearful, more flighty? Well, it turns out that they had a long history of being hunted for their bills, used as decorations by Indigenous peoples.

Is it possible that Ivory-billed Woodpeckers could have held out for awhile longer and recovered in number by expanding their home range areas in less than fully favorable habitats, such as in regenerating southern forests? Perhaps they tried, but too many perished in those less protected forests. Or perhaps it was just bad luck that time ran out for the Ivory-bill Woodpecker.

Ecological Impoverishment

One thing is clear from this tale of two woodpeckers: wild species vary in their ability to withstand human impacts for a host of possible reasons, most of which have to do with differences, sometimes subtle, in their basic biology and behavior.

Wild animals (and plants) tend to sequentially drop out of an environment as it’s increasingly artificialized by humans. The order in which they do corresponds to their comparative vulnerability to human presence. There are proximate causes of wildlife loss such as shooting, poisoning, and flat out elimination of habitat; intermediate causes such as partial removal or degradation of habitat; and ultimate drivers like urbanization and climate change resulting from human population and economic overgrowth.

Northern Florida, where I live, exemplifies how a wildlife community becomes truncated by a growing human presence. I characterize my present surroundings as being part country and part suburban.

Gone — Red wolves, Florida panthers, and black bears exist no longer (although the bears still live elsewhere in my region). Large predators are typically the first to go when people “settle” an area. The Ivory-billed Woodpecker, of course, is gone, as is the Carolina Parakeet, which was eliminated by forest clearing and shooting. These beautiful birds were killed for the garment industry (colorful feathers), to protect crops (the birds liked fruits, flowers, nuts and corn), and even out of anger over their noisy chatter.

Going —Many if not most wild species face a diminished future. The reason has to do with widespread displacement of them by agriculture, urbanization, logging, and other landscape-altering factors, death and disturbance related to night lights, noise, and vehicles (including boats and aircraft), pollution, pesticides, spread of non-native species and diseases, and losses due to sheer human intolerance. If these factors were not enough, wildlife now faces further difficulties related to anthropogenic climate change. In truth, we sometimes never know what is being lost because, as some disappear, a living web is broken and others follow. These cascading effects often impact less noticed wildlife, like many insects.

Where I live, victims of human crowding appear to include gopher tortoises, box turtles, water moccasins, alligators, beavers, bobcats, gray fox, barred owls, swallow-tailed kites, bald eagles, wood storks, fireflies, and bees, and, yes, pileated woodpeckers, as well as many others.

The Final Few — White-tailed deer, coyotes, raccoons, northern cardinals, mourning doves, and others have resisted, even prospered in the wake of civilization’s onslaught. But they too have limits, and will decline or vanish entirely from lands that are further urbanized, commercialized, or industrialized. The best among us create wildlife-friendly gardens, fight to save patches of forest that allow birds to safely traverse agricultural areas, and take other such measures to help wildlife. Hopefully, the “final few” will be many. But mitigation alone won’t save countless other living beings blown or swept away by our overgrown civilization.

No one in my neck of the woods remembers the Ivory-bill Woodpecker or the Carolina Parakeet. Most more or less appreciate the local fauna and flora but don’t like snakes or alligators or possums, or poison ivy, and prefer they be gone. Some kill every water moccasin or copperhead snake they see. Others cut “their” big trees down, expand their lawns, and (ironically) hang up bird feeders. The old timers around these parts can tell you about days now gone when there was a lot more wildlife. Even black bears, and maybe a panther or two.

A new house just went up nearby. Another is about to. Other lots are for sale, and, given Florida’s growing population and land development proclivities, more trees will fall and more roads will be paved. Nature-lovers and conservationists will fight developers for the last wild acre. The sounds and sights of forest critters will lessen, some will end. Most younger folks who move here will never know the difference.

A Different Future

I refuse to end on such a gloomy note. We simply can’t accept that dismal future. A change in the human heart will come, believe me. Ours is a destiny to fulfill.

You are what your deepest desire is. As your desire is, so is your intention. As your intention is, so is your will. As your will is, so is your deed. As your deed is, so is your destiny — Vedic text.

Great write up! You have to go to this link and read the very end. http://www.somesuchstories.co/story/musuem-of-extinct-animals

It's about the last Ivory-bill searches.

Very much enjoyed your writing; thank you for the enlightenment.